A National Park for Iceland's Central Highlands

| All, DISCOVER ICELAND

This week we want to discuss an issue that is very dear to us. We want to guarantee the preservation of the Icelandic Highlands for generations to come, and we wanted to take some time to you a little bit about what the project is, why it is necessary and how we are helping to make this project a reality. If you want to be a part as well, you can follow the link at the end of this post to the petition, which has gathered over 15000 signatures.

A National Park for the Icelandic Central Highlands

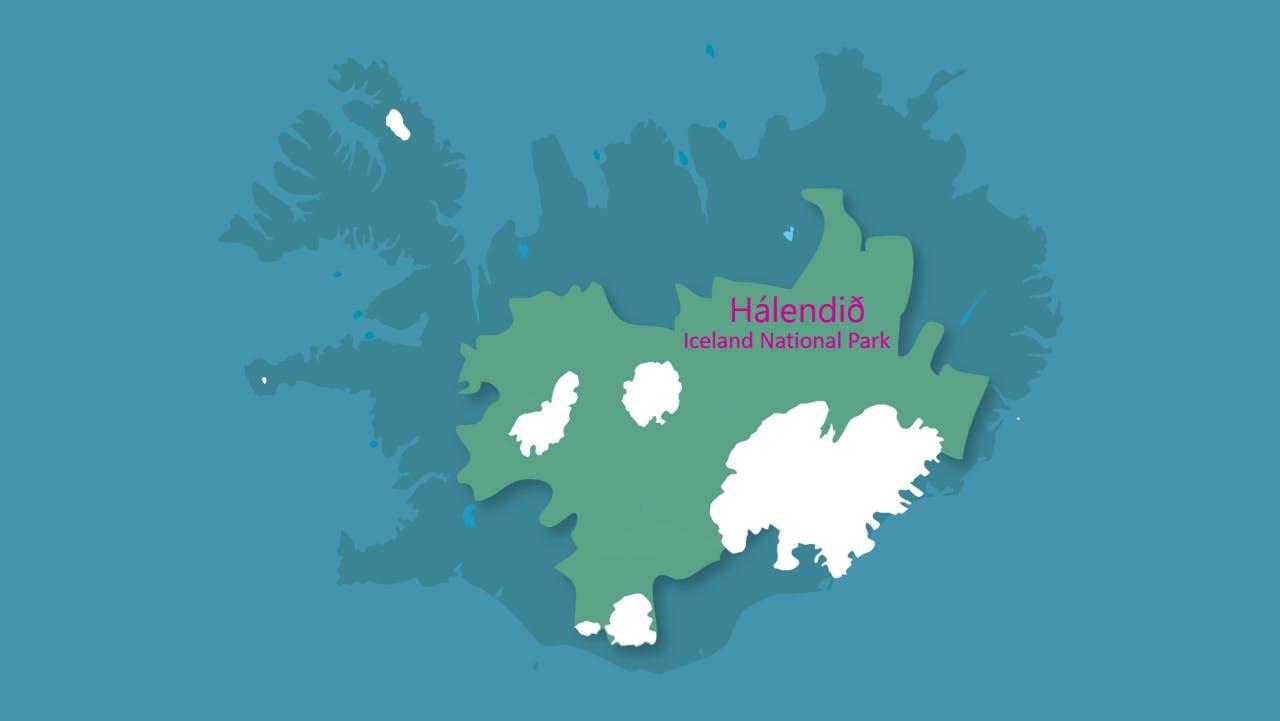

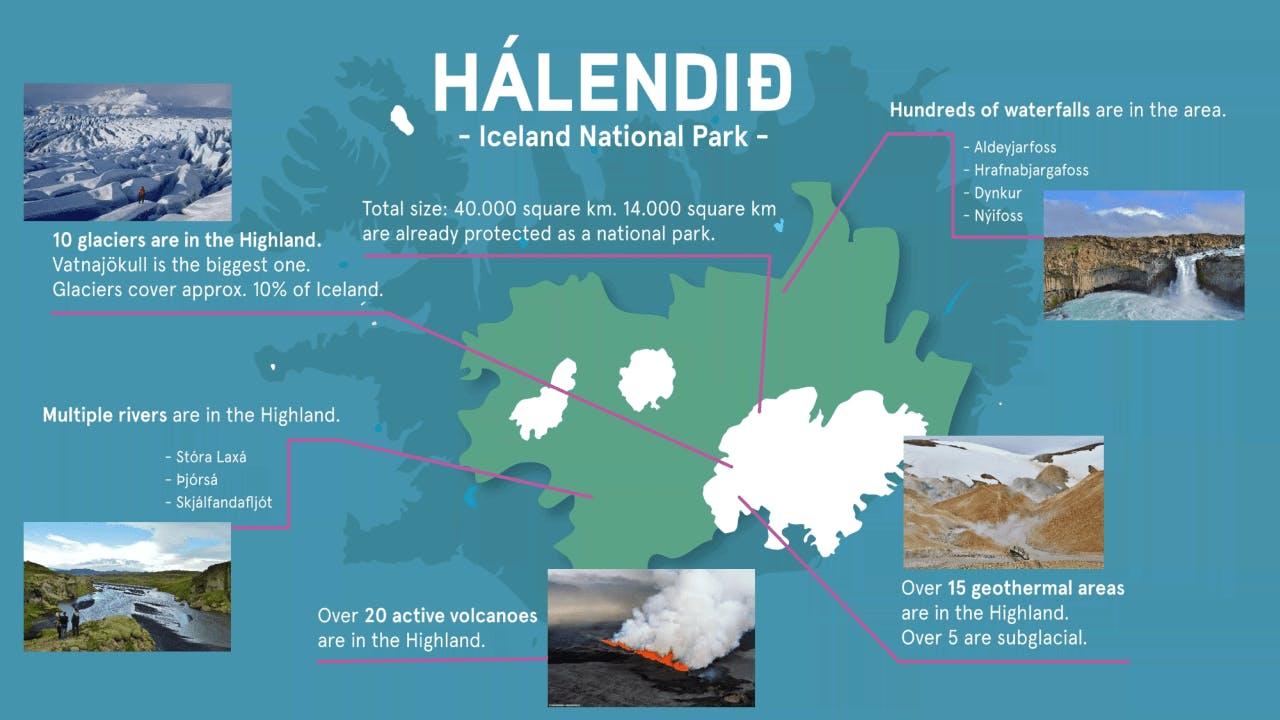

Iceland is a remarkable country. You would be hard-pressed to choose an area that you could say is the “most beautiful” of all. However, there is one region that could certainly contend for this title; it occupies 40.000 km2 of the island (103.000 km2) and is one of the largest uninhabited and uncultivated territories in Europe. It is Europe’s largest wilderness. Europe’s last great wilderness.

We are, of course, referring to the Icelandic Highlands. The highlands feel like the last frontier. A wild, fierce and unforgiving landscape of mesmerizing beauty, the highlands will likely change you as a person.

Currently, there is a project, a desire, and even a proposal to turn this vast and miraculous area into a national park. Iceland already houses Europe’s second-largest national park; Vatnajökull National Park was opened in 2008 with an area of 12.000 km2 and has, in subsequent years, been expanded to 13.920 km2 or approximately 14% of Iceland.

The Highland National Park will massively add to this area, either by being amalgamated together into one large national park. The other option is to create them as two national parks serving the same function, both of which are potential proposals being debated.

What is the purpose of the park?

Establishing a national park in the highlands is about protecting it not just from heavy industry, but in general, so that we can have a use for it for future generations, a use that has the potential to be sustainable. Accessible for leisure activities and general enjoyment of the area, with the restriction that it doesn’t damage the area.

There is also a desire to sustainably increase the infrastructure of recreational facilities within the territory of the National Park. The highlands area is a very sensitive area, and it can’t tolerate a large amount of traffic, whether it’s wheels or feet.

This is as much about making the park accessible as well as about preserving the landscape for future generations of Icelanders, and it is an area that has a big importance for most Icelanders.

Highlands under threat

Iceland’s geothermal and hydroelectric power potential has long been recognized, and it is these sources of renewable energy from which Iceland derives its low cost of residential energy and high standards of living.

The darker side to recognizing the power of these resources is that they have been identified, and indeed used, as energy sources for large-scale development and industrial mega-projects, such as in the aluminum and ferrosilicon industries: energy intensive-industries that require good baseload power.

The importance of protecting Iceland’s highlands came into strong focus in 2003, when a project was backed by the National Power Company and Alcoa to build a smelter and dam complex in the East of Iceland. The Kárahnjúkastífla Dam is a five-dam complex, the largest of its type in Europe, standing 193 meters (633 ft) tall with a length of 730 meters (2,400 ft) and comprising 8.5 million cubic meters (300×106 cu ft) of material.

The project and its various voices were covered extensively by National Geographic in 2008. After some years have passed, the project continues to be heavily criticized for the environmental impact and use of foreign workers. The use of foreign workers greatly undermines one of the main premises of the initial argument for the project which was that it would lead to a rise in long-term employment in the area.

As for environmental impacts, the dam complex had a tremendous effect on the local area.

The dam flooded an enormous area and resulted in the displacement of a large population of native wildlife.

An awareness of the dam and environmental impacts thereof have elevated the conversation about the highland national park to a much higher level. This is also because there are further proposals to develop the highlands in other ways. These include, but are not limited to:

- Establishing an over-land 220-400 KW power line through the central highlands

- Proposals for more hydroelectric dams to supply heavy industry

- Developing the road networks in the highlands, laying paved roads (all highland roads are unpaved)

Elevating the highlands to National Park status automatically and greatly restricts all construction and development of the physical landscape. Different areas will likely be subject to different levels of protection, with particularly sensitive areas being allocated a higher protection status.

How far along is the Highlands National Park project?

The project is far from being just an idea, is very much in the works, and is well underway.

The ministry of environment has created a committee to prepare the way for the legislation and a formal planning process.

The Icelandic Nature Conservation Association and Landvernd, the two big major nature conservation associations in Iceland joined forces on the issue and has received the backing of the minister for the Environment

The administrative side of the project is potentially tricky since the area in question being to 22 different communities. All of the stakeholders have to be brought to the table and the conversation needs to proceed from there.

Icelandic Mountain Guides supporting the push to National Park status!

As environmental stewards in Iceland, Icelandic Mountain Guides has been deeply involved with conversation efforts in different parts of Iceland. The main focus of our efforts, executed through the Environment Fund and supported with our Environmental Policy in all of our activities, has been in the highlands. One of our founding partners represented the Association for Icelandic Tourism through the entire dialogue

Get involved! Sign the petition!

If you want to help make your mark on the push to make the highlands a national, you can join over 15000 people in signing the people/making a donation here!

Keep me informed about the Icelandic Mountain Guides Blog

Outdoor adventure in Iceland is our specialty. Subscribe to our free monthly newsletter to learn when to go, what to do and where to have the best adventures in Iceland.

Related Blog Posts

Related Tours

Laugavegur & Fimmvörðuháls Combo Tour